ANICA

Nurturing Communities and Trade for Over a Century

ANICA’s roots trace back long before Alaska attained statehood in 1959. It was in the early 1900s, at the dawn of that century, when Indigenous communities in Northwestern Alaska lived in modest, scattered groups. These communities often consisted of a solitary family or, on occasion, just a couple of families. During the summer, these extended family units would embark on seasonal migrations to engage in the harvesting of resources from the seas, rivers, and nearby mountains. Those residing along Norton and Kotzebue sounds, as well as the western extremity of the Seward Peninsula, relied heavily on spring hunts for seals, whales, and walrus, complemented by fishing activities during other seasons.

In contrast, inland communities in the upper Kobuk River Valley and along the Fish River on the Seward Peninsula thrived on hunting caribou, smaller game, avian species, and the cyclical salmon runs, among other fish varieties. These communities not only adeptly adjusted their lifestyles to optimize their yields from both maritime and terrestrial environments but also capitalized on their geographical positioning to assume the central role of traders between Alaskan Natives dwelling further from the Bering Strait. Periodically, they engaged in trade with Siberian Natives for Russian merchandise. Sheshalik, situated near modern Kotzebue, hosted an annual trading fair that attracted over two thousand Native individuals from the entire region, including some from far-off Asian territories. This rich tradition of trade honed their skills in negotiations when interacting with early Westerners and intrepid whalers who ventured into the region. By the 1880s, the inhabitants of the Bering Strait region had seamlessly incorporated an array of Western products into their daily lives.

To access these Western commodities, Native individuals sought employment with whalers and the limited number of other Western settlers who ventured into the region. During the late 1890s, it is believed that perhaps as much as half of Alaska’s Native population north of the strait engaged seasonally in the whaling industry, enticed by the allure of Western goods. This influx of individuals from the remote reaches of the Noatak and Kobuk valleys even led to some Natives forming their own whaling crews and occasionally hiring Westerners as their workforce. However, this intensified whaling activity exacted a heavy toll, severely depleting the primary food source of the coastal Inupiat diet and exposing Native communities to certain unwelcome aspects of American culture.

In response to these evolving circumstances in 1890, Sheldon Jackson, a Presbyterian missionary who assumed leadership of the U.S. Bureau of Education in Alaska, embarked on a mission to recruit missionaries who could also serve as educators in three Native centers: Wales, Point Hope, and Barrow. By 1903, the number of Native schools had grown to twenty-three. The Bureau of Education initiated initiatives to stimulate Native industries and promote marketing skills. Teachers were charged with the responsibility of imparting education to Alaska’s Native populace while safeguarding their cultural heritage. These schools garnered popularity and evolved into focal points for settlement. When the agency undertook the construction of schools along the Noatak, upper Kobuk, and Selawik rivers in 1907 and 1908, local residents quickly followed suit, erecting permanent residences and establishing enduring villages. These communities perceived the schools as potential hubs for trade and income generation. Teachers dabbled in trade, bartering Western goods for more suitable Native attire and sustenance. On occasion, teachers also requisitioned furs and food for their personal subsistence and assistance in the transportation of their annual allocations of personal effects and school equipment to the villages.

In the modern era of ANICA, elders fondly recollect the times when BIA (Bureau of Indian Affairs) vessels transported teachers and supplies to the villages each summer. Teachers earned the highest esteem, as they demonstrated sincere concern for the well-being of Native inhabitants and rendered invaluable medical care through their modest medicine chests. In various regions, the initial American missionaries, doubling as government teachers, administered medical care to numerous local patients. The Alaska Native Service, which eventually transformed into the BIA, dispatched teachers to manage these newly established schools. Additionally, these schools hosted small Native stores stocked with essential provisions accessible to village residents. In addition to their pedagogical duties, teachers extended their support to the nascent Native store managers. Nevertheless, during World War II, some of these Native stores endured temporary shortages of supplies due to the absence of teachers. Village leaders discerned the necessity of establishing an organization to ensure that the stores remained well-stocked with essential goods at competitive prices.

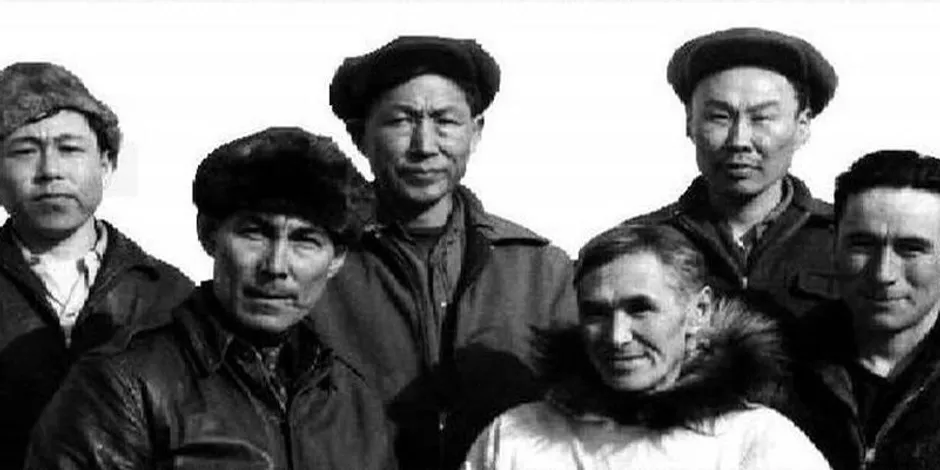

In the summer of 1947, a congregation of village leaders congregated in White Mountain to deliberate on the formation of a Cooperative. Representing a multitude of villages, notable individuals such as Roy Ashenfelter and Abraham Lincoln from White Mountain, Simon Bekoalok from Shaktoolik, Xavier Pete from Stebbins, David Saccheus from Elim, and Frank Degnan from Unalakleet assumed pivotal roles. These venerable figures, affectionately dubbed the ANICA Founding Fathers, successfully orchestrated the inception of the Alaska Native Industries Cooperative Association. Their aim was to furnish village stores independently of the BIA. The ANICA Founding Fathers discerned that by uniting as a collective entity, they could attain superior success and prosperity compared to individual villages. Moreover, they displayed foresight by embracing contemporary methodologies for the betterment of their constituents in the villages they represented. Initially, the first village stores relied on the BIA Northstar for the annual delivery of fundamental grocery items such as coffee, sugar, and flour, coinciding with the arrival of BIA school teachers and supplies by boat.

Cooperatives are founded upon the principles of self-help, self-accountability, egalitarianism, and solidarity. In consonance with the legacy of the ANICA Founding Fathers, ANICA upholds ethical values including integrity, societal responsibility, and compassion for others. The organization’s core mission is to advance the interests of ANICA Native stores. ANICA heeds the lessons of its history and diligently endeavors to fulfill the pledge made by its Founding Fathers over six decades ago.

Photos courtesy of ANICA Inc., Delta Discovery and Grid Adrenal.